Navigation and useful materials

Back to the Future. 12 Archaeological Treasures that Russia Took out of Ukraine

In the lands of modern Ukraine, ancient peoples with a developed culture lived and interacted, turbulent historical events took place. They were significantly more active than on the lands of the central Russia because of their periphery relative to the centres of civilization. It is not surprising that the imperial centre, which eventually appeared there, “absorbed” the jewels from the seized territories, as all the empires of that time did.

However, even today, Russia has not abandoned its imperial habits, presenting the monuments found in Ukraine as Russian, in particular, for a foreign audience. This is also used as an argument for “historical rights” to Ukrainian territories.

The robbery of museum exhibits, as it happened in Melitopol, Kherson, or even the destruction, as in Mariupol, once again reminded of the systematic seizure of treasures by the imperial centre during the reign over Ukraine.

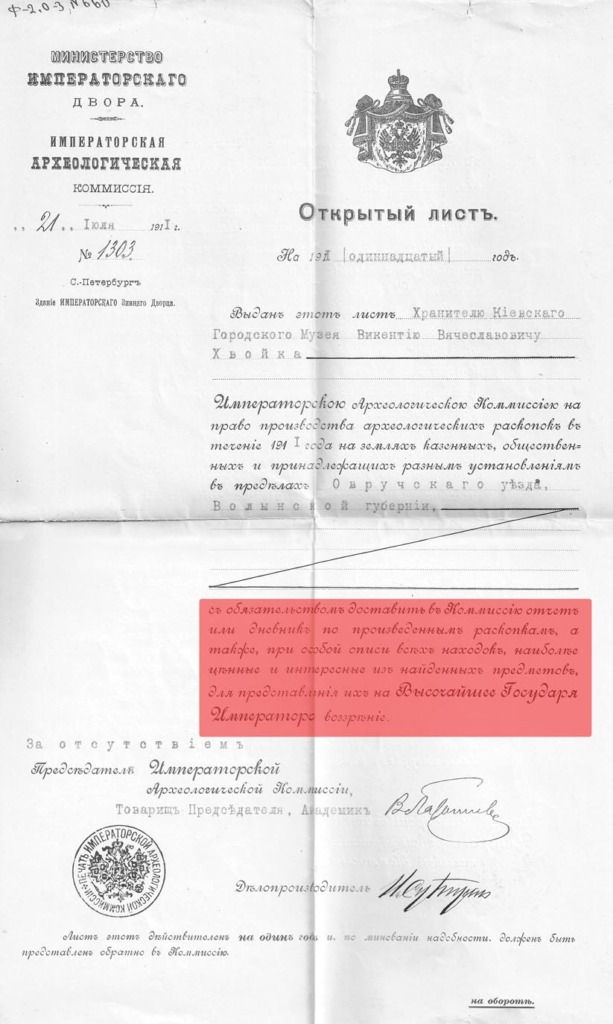

Beginning in 1889, all discovered finds were automatically brought to the attention of the Imperial Archaeological Commission (IAC), whose members decided their fate. No wonder, the collections of museums in St. Petersburg and Moscow were actively replenished.

Many artefacts — sources for the reconstruction of the ancient history of Ukraine — were removed from Ukrainian museums and transferred to Moscow during the 1930s. Some finds from the collections of Ukrainian museums that the Nazis took out during World War II, after being returned, “surprisingly” found themselves in Moscow and Leningrad.

After the seizure of Crimea by Russia in 2014, these territories became the object of “close attention” of Russian researchers as far as archaeology was concerned. For the most part, collections from illegally excavated Crimean finds are taken to the territory of Russia by Russian invaders.

Nowadays, during the large-scale Russian aggression, we have documentary evidence of the seizure (“evacuation”) of collections from museums located in the temporarily occupied territories of the mainland of Ukraine: Kherson region, Luhansk region, etc.

The Ukrainian Association of Archaeologists within the project “The archaeological heritage stolen by Russia” has compiled a list of treasures that at different times were taken from Ukraine to Russia. The Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security offers to get acquainted with the history of 12 monuments that Russians appropriated.

1. Rhyton of Kropyvna (Poltava)

Kropyvna (Poltava) rhyton is almost the first Ukrainian find that got into the Russian museum.

A rhyton is a vessel for drinks or ritual libations in the form of a curved horn, which ends with a horse’s front part image. The find, along with other items, was discovered in 1746 within the boundaries of the Kropyvna Sotnia of the Pereyaslav regiment.

Today, Kropyvna is a village in Ukraine, in Zolotonosha district of Cherkasy Oblast. According to official documents, it was discovered by shepherds in the sand, but there is also a version that the rhyton comes from a burial mound, where saltpetre was mined.

The Rhyton of Kropyvna is made of silver with gilding in the 4th century BC, most likely in Thrace, the modern territory of Bulgaria; its weight is 902 grams.

The item was taken by Russian authorities to St. Petersburg and to the academic Kunstkamera. Later, the artefact became part of the Imperial Hermitage collection, where it is still kept under the name of the Rhyton of Poltava.

2. Ornithomorphic gold plate and sword from Lyta Mohyla

Russia’s appropriation of artefacts of ancient Ukrainian history begins simultaneously with the first systemic excavations in the steppes of Ukraine — already from the second half of the 18th century from the excavations of Lyta Mohyla, also known as the Melhunovskyi Kurhan.

Located in the modern Kropyvnytskyi district of Kirovohrad Oblast, it is one of the most famous burial mounds. Its research marked the beginning of focused archaeological excavations in the territory of the Russian Empire and laid the foundation for the study of Scythian antiquities.

The ornithomorphic gold plate, as well as the golden sword, were in the treasure, found in a stone cist under the top of the mound. In total, 17 massive gold plates in the form of eagles, plates with images of monkeys, a gold tiara and more were found.

It is assumed that these artefacts belong to the second half of the 7th century BC and were military trophies of the Scythians, got during their campaigns in Asia Minor. The precious artefacts were made in the Assyrian and Urartian style.

3. Golden comb from Solokha burial mound

The mound was located near the village of Velyka Znamianka, now Zaporizhzhia Oblast, on the left side of the Dnipro, at a distance of 10 km from Enerhodar. The village is currently occupied.

Such a work of goldsmithing is a kind of high level of Greek craft on the order of the Scythian aristocracy.

The eathen mound of Solokha kurhan was 18 m high and 110 m in diameter. It is here that unique examples of Greco-Scythian torevtics were found.

Nevertheless, today you will not see these items in Ukrainian museums because they adorn the collections of the State Hermitage. In most catalogues authored by Russian researchers, its place of origin is indicated as the “Northern Black Sea Region” or “Dnipro Region,” without mentioning Ukraine.

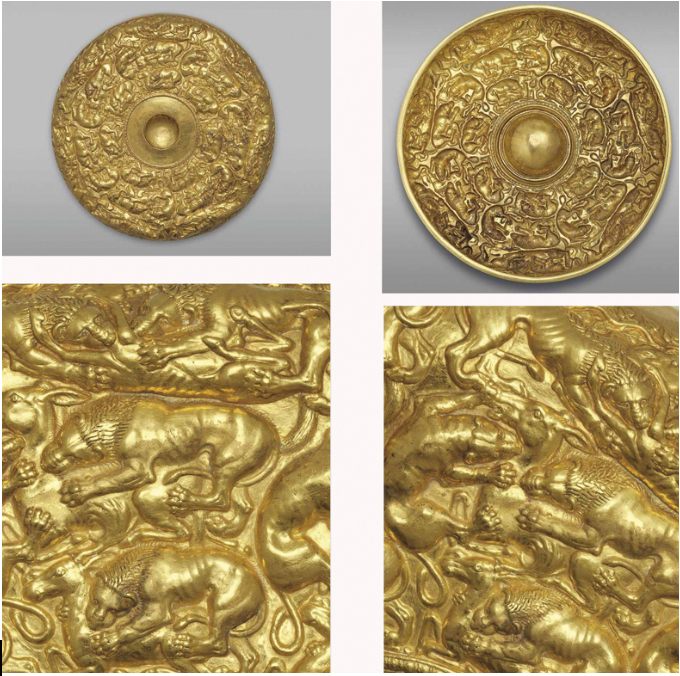

The comb is not the sole astounding discovery from the Solokha burial mound. A unique gold-sheathed sword was found there, as well as a golden phiale and many other unique items.

A phiale is an ancient Greek flat sacrificial bowl without handles. It depicts a relief image of predators attacking ungulates.

4. Zoomorphic fibula from the first Mykhalkiv treasure

This is a clasp that was also a decoration. It is part of the so-called Mykhalkiv treasure — jewels that belong to the Hallstatt culture. The fibula, as well as all the treasure, was found in 1878 near the Mykhalkiv village of Borshchiv district in the Ternopil region.

The story goes that after a heavy rainfall, girls saw the jewellery. They did not dare to touch the treasure and called their mother. A surprised widow went with her daughters to that place and came across gold things in the washed-out clay. Raking the rain-soaked clay, she found more and more new things and put them into the hem. Having collected six things, she went to the moneylender.

On hearing this, the villagers went to the landslide place to look for gold things. The authorities managed to seize the bulk of the treasure’s items, but it is not known how many of them disappeared without a trace. Twenty years later, in 1897, another treasure was found near Mykhalkiv. The total weight of the two finds was more than 7 kg.

The Mykhalkiv treasures became the gem of the archaeological collection of the Didushytski Museum in Lviv. In 1940, after the occupation of Lviv by the Soviets, the “Lviv” part of the treasure was transferred to Moscow. Today, the jewel is kept in Russia, most likely in Moscow.

5. Golden earrings from Olbia

Olbia is one of the most important poleis of the ancient Greeks in the Northern Black Sea region. Today, the territory with excavations of Olbia is a historical and archaeological reserve, which is located in Mykolaiv Oblast, on the right bank of the Bug estuary.

Systematic excavations on the territory of Olbia have been conducted since 1901. From that time until today, the most valuable Olbian discoveries were usually taken to the museums in Moscow and St. Petersburg (Leningrad). Less valuable finds did end up in museums of Odesa and Mykolaiv.

Among the many ancient objects from the excavations of the ancient poleis of the Northern Black Sea region, the imperial centre exported gold earrings of the 6th century BC from the Olbian necropolis — an ancient cemetery.

The jewellery was found in one of the graves in 1913. It is likely that the burial belonged to a wealthy female resident of the polis. Ear ornaments were found on both sides of the head. These pairs of jewellery were worn over the ear so that a large part overlapped under the ear.

In the middle of the shield, there is a figure image of a lion’s head front view with an open mouth. Apart from the earrings, rich burial equipment was discovered that consisted of a gold ring, a gold necklace, several gold plaques, a bronze mirror, and ceramic dishes.

It should be noted that at least five similar paired ornaments of the same type, found at the archaic Necropolis of Olbia were taken to the Hermitage. The Russian Museum currently does not exhibit these finds, so they are probably kept in the museum fund collections.

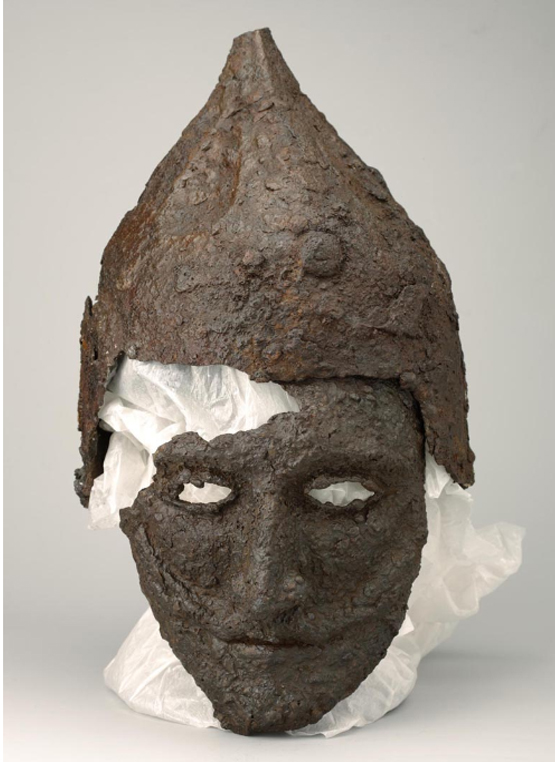

6. Helmet and iron mask from Kyiv region (12 th — early 13th century)

The helmet and iron mask are artefacts of the history of the Black Hoods that lived in Porossia, a forest-steppe part of Kyiv region. Oakwoods and ravine forests are combined with steppes. During the princely times, various tribes of nomads came here from the Great Steppe. Kyiv chroniclers called them Black Hoods or Our Pagans, emphasizing that most of these nomads remained pagans.

Numerous mounds of the Black Hoods are scattered in the Southern Kyiv region between the rivers Ros and Stuhna.

Since 1888, Nikolai Brandenburg “ravaged” about 300 kurhans for the needs of the Artillery Historical Museum in the steppe part of Porossiya — the Kaharlytskyi Steppe.

The helmet and the mask were found in 1892 near the Lypovets village, in the Kyiv region, now it is Obukhiv district. Excavations were conducted by O. N. Makarevych.

In 1932, the Brandenburg’s Collection, which included both the mentioned items and artefacts from the territory of present-day Cherkasy region, was transferred to the State Hermitage, where it is stored to this day.

Since 2017, Russians have been flaunting displaying the iron mask from Lypovets village in the permanent exhibition of the Hermitage. Russian museologists still indicate Russia, Dnipro region, or Malorossiya as the places of discovery of the items from the territory of Ukraine.

Unfortunately, there are almost no archaeological finds in Ukrainian museums that reveal the material culture of the Black Hoods. As it is easy to guess, the lion’s share of them was taken to the imperial museums of Russia at the end of the 19th century.

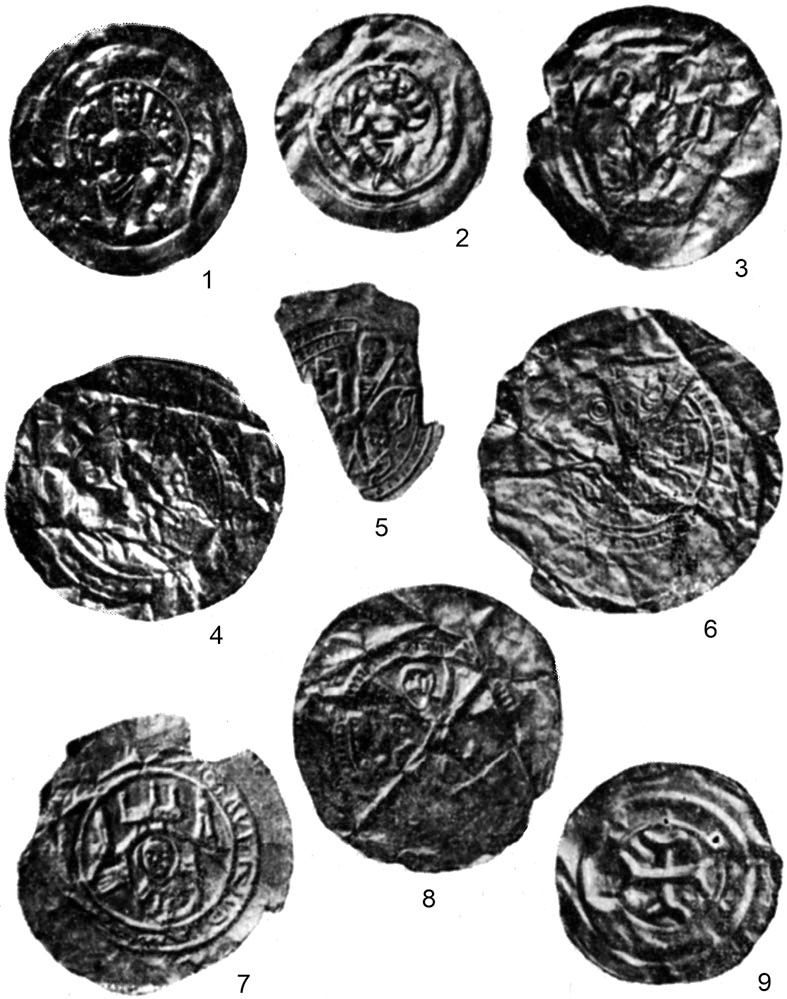

7. Khotyn Treasure of coins

In 1889, on the territory of the city of Khotyn, now Chernivtsi Oblast, burgher Arkhyp Ozarchuk found a large treasure of silver coins when he cultivated the leased land.

In total, the treasure included 1,000 to 1,600 coins. More than 900 whole and fragmented specimens remain in the collection of the Hermitage.

Among the coins, 888 bracteates were identified. Bracteates are silver coins minted on a thin circle of metal on only one side with an upper stamp on a soft surface, due to which the image on the obverse turned out to be convex, and on the reverse — concave. They had a diameter of up to 40 – 45 mm and a weight of about 1 g.

These coins got to the Galicia-Volyn principality from the German lands through Hungary, in particular Transylvania. They can reflect the way of Bulgars from Hungary to Kyiv and further to the Volga.

It is assumed that the treasure was hidden in 1217 – 1218 by one of the participants of the fifth crusade, led by the Hungarian king Endre II. Obviously, the Khotyn deposit is connected with the vicissitudes of King Danylo’s struggle against Hungarian invaders and boyar opposition in 1230.

Despite official appeals to the Hermitage management, Russians systematically refused Ukrainian scientists even to get acquainted with this collection of medieval coins from Khotyn.

8. Lev (Lion) cannon of Hetman Mazepa

If the appearance of archaeological finds in Russian museums was a result of the burial mound excavation rush and the search for gold treasures, then the appropriation of artworks by Russians in early 18th century happened for the most part through systematic barbarian looting of Ukrainian cities after the defeat of the uprising of Hetman Ivan Mazepa.

Among the items stolen by the Russian “nobles,” Cossack cannons hold a special place. These are outstanding examples of Ukrainian baroque foundry made by the order of Hetman Ivan Mazepa and Hadiach colonel Mykhailo Borokhovych. The lion’s share of these works of foundry art are kept in museum institutions in St. Petersburg and Moscow.

Thus, the Russian Empire appropriated the bronze long-barreled 16-pounder Lev (Lion) cannon, which belonged to the General Military Artillery of the Hetmanate.

Karp Balashevych cast it in 1705 in Hlukhiv, today it is Sumy Oblast, by the order of Ivan Mazepa and richly decorated it with baroque ornaments and heraldic signs of the Hetman. Like other Ukrainian cannons and kleynods of the Mazepa era, these works were captured by Russians when they plundered Ukrainian towns in 1708-1709.

After these events, the artillery was taken out of Ukraine. Some of the large-calibre guns were destroyed in Baturyn. All Zaporozhian artillery was confiscated after the storming of Sich on May 14, 1709.

“Moscow General Menshikov brought to Ukraine all the horrors of revenge and war. All of Mazepa’s friends were dishonourably tortured. Ukraine is drenched in blood, destroyed by looting, and shows everywhere a terrible picture of the barbarism of the victors,” wrote Hanoverian diplomat Friedrich Weber.

Menshikov took Mazepa’s library and a huge collection of works of art and weapons. Later, the things stolen from the Hetman and the Ukrainian foremen formed the basis of Menshikov’s private collection at his residence in St. Petersburg. Subsequently, these things ended up in the Hermitage and other museums and became the backbone for the development of the museum business of the Russian empire.

Already during the Soviet times, in the wake of the pretended struggle with the imperial past, the government of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1929 appealed to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic with the demand to return a number of artistic, historical, and cultural values to the Soviet Ukraine, which had been taken by tsarist officials to Moscow and St. Petersburg. However, even despite the agreement of the Parity Commission in 1930, Russians didn’t return many antiquities related to Ukraine and its history. That includes the Lion Cannon of foundry masters from Hlukhiv, which is still kept in the museum-reserve in the Kremlin.

9. Silver vessel depicting a dog-bird and a tree of life (Silver vessel depicting a fantastic creature Senmurv and the tree of life, 3rd – 7th centuries)

In 1823, near the Pavlivka village of the Starobilsk district, Luhansk Oblast, while ploughing a small burial mound, local villagers found a set of items: a silver and gilded wine jug with the image of the mythical deity Senmurv (dog-bird), two silver bowls, and a wooden saddle.

A silver narrow-necked wine jug had a duckbill spout and an elegantly curved handle and stem. Two oval embossed and carved medallions depicting Senmurv decorate the body of the vessel. They are separated by a stylized tree of life.

This find was made by Persian masters during the reign of the Sassanid dynasty in Iran, 3rd–7th centuries. It could have got to the lands of present-day Ukraine either as a result of trading or as the property of migrant nomads. These exquisite examples are rare finds in our territory.

The settlements of Starobilsk district are indicated as the place of finds, which are still in the Russian Hermitage, without any indication that this is the territory of modern Ukraine.

10. Little man from the Chorna Mohyla

The famous Chorna Mohyla, the mound that still stands in Chernihiv, without exaggeration, can be called the most remarkable of the excavated Ancient Rus burial mounds. This burial mound is almost the only one that we can classify as princely, dated to the second half of the 10th century. The research carried out in 1872 – 1873 on the site discovered a complex funeral rite of the cremation type and numerous finds.

Among these items was a figurine, whose details, due to a significant amount of oxides covering its surface, were difficult to see. It could be only distinguished back then that this little man was sitting with folded legs and hands in front of his chest.

Initially, the figurine was cleaned to such a degree to see that it was indeed a man. He was holding his long beard in his right hand and clutching some object that had been lost with his left hand.

On the territory of Ukraine, such a figurine is the only and unique find and has great significance for the history and culture of Rus. Such figures are rare finds. In addition to the Chernihiv one, there are only five of them in the world. All analogies come from Scandinavian countries and regions, where Scandinavians were numerous during the Viking Age. According to one version, this is a figurine for the Scandinavian medieval board game hnefatafl.

By appropriating artefacts from the Chorna Mohyla, Russians are trying to appropriate the history of the princely era.

11. Mosaics and frescoes from the destroyed St. Michael’s Cathedral

St. Michael’s Cathedral in Kyiv was built in 1108 – 1113 during the reign of Prince Sviatopolk Iziaslavych. One of the largest in ancient Kyiv, the monastery was princely and served as a burial place for Kyiv rulers during the 12th century.

Soviet authorities destroyed St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral with explosives on August 14, 1937. In the spring of 1937, the State Ukrainian Museum in Kyiv (now the National Art Museum of Ukraine) opened an exhibition of art monuments of Kyivan Rus. In particular, mosaics, frescoes, and two ancient slate reliefs from St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral were displayed there.

After Pymon Rudiakov, the director of the Ukrainian Museum, was accused of Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism and executed in Bykivnia on December 22, 1937, the museum’s exhibition was dismantled. Part of the exhibits was transferred to St. Sophia Cathedral, which was already a museum at that time. Another part of the mosaics and frescoes was sent to Moscow for a temporary exhibition organized by the State Tretyakov Gallery. Russians never returned them.

At the end of the 1990s, St. Michael’s Cathedral was reconstructed in Baroque architectural forms. Even though some unique mosaics and frescoes were preserved in Ukraine, and in the early 2000s, several monuments were returned to Kyiv, Russians are not giving back a range of works of monumental art from the time of Kyivan Rus.

The aggressor country continues to flaunt the Ukrainian heritage of the princely era, shamelessly passing it off as its roots. In particular, frescoes, mosaics, and a slate slab from St. Michael’s Monastery are displayed in the permanent exhibition on the “Ancient Rus Art. Pre-Mongol period” in the Tretyakov Gallery.

12. Leox stele from the Kherson Museum

In October 2022, the Russian occupation authorities announced the “evacuation” of the Kherson Regional Museum of Local History. Russians looted the archaeological and historical expositions, having stolen archaeological finds from different periods, a numismatics collection, and historical weapons. Although most of the archaeological collection was kept in the Museum storage and thus preserved, some iconic and recognizable items disappeared.

Among the artefacts stolen by Russians is the unique Leox stele (the early 5th century BC), found during excavations at the Olbia necropolis today — Mykolaiv Oblast. It was transferred to the Kherson Museum in 1895. The current location of this museum item is unknown.

The stele is made of a rectangular marble slab with relief images on its two sides and inscriptions on the side faces. One side depicts a naked warrior, resting his right hand on a spear and holding his left hand on his waist. The other side shows a profile image of a figure in Scythian costume.

The upper and lower parts of the slab were lost, and thus the images of the heads and lower legs of both figures are missing. If the interpretation of the naked figure does not raise doubts (it is Leox), the researchers have still not reached an agreement about the other figure. They consider it a Scythian / Greek / Hellenized barbarian or even an Amazon.

The reconstruction and translation of the inscriptions on the side faces showed the phrases that were written there. The one side writes, “I stand, a monument to courage, and say that Leox, son of Melpagoras, died defending the city and lies far away,” on the other side — “I am the monument to Leox, son of Melpagoras.”

***

Any seizure or destruction of monuments during the war is prohibited. This is evidenced by Article 56 of the Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, which is an annex to Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land of 1907.

According to Yevhen Synytsia, Head of the Board of the all-Ukrainian Association of Archaeologists, Ukraine needs to create a separate state institution that will deal with the restoration of rights to the taken valuables and their return.

He agrees that Russia will not return the loot voluntarily, and the established mechanisms of coercion do not exist even for the enforcement of court decisions. However, in his opinion, the scientific and cultural isolation of the violating country can be one of the mechanisms of such coercion.

In the end, there will be a practical question of compensation by Russia for the losses caused by aggression. And in addition to reparation payments, Ukraine has the right to demand the return of valuables that were taken both recently and during the reign of the imperial centre.

To do this, according to Yevhen Synytsia, domestic legislation should be adapted to international law, in particular, the Nicosia Convention of 2017, which is designed to prevent illicit trafficking in cultural property.

Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.