Navigation and useful materials

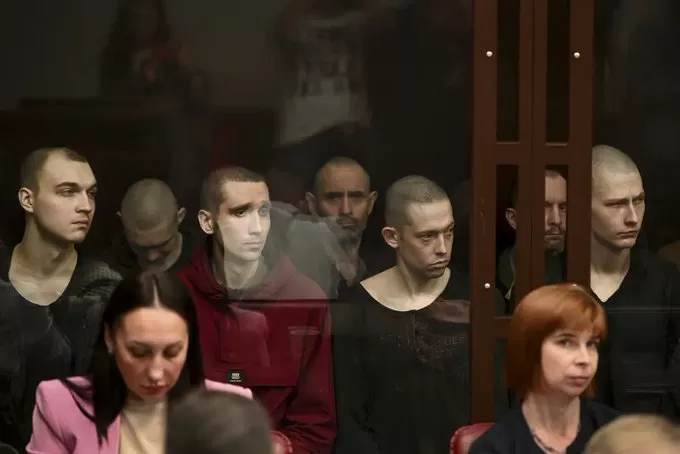

On June 15, 2023, in the Southern District Military Court of Russia in Rostov-on-Don, the trial of 22 captured soldiers of the Azov regiment of the National Guard of Ukraine began.

For this performance, the Russian invaders chose 14 men and 8 women from Azov, who in May 2022 ceased resistance on the territory of Azovstal in Mariupol and found themselves in Russian captivity.

According to the agreement, which preceded the order of the Ukrainian command of the garrison to stop the defence, Russia had to ensure a safe exit for the military and proper conditions for their stay in captivity.

This agreement was repeatedly violated by the Russian side, in particular, by committing a mass murder of Azov prisoners in Olenivka in July 2022, as well as abusing and bringing to a state of physical exhaustion the remaining prisoners of war, which was established by medical examinations after the release of some of them as a result of exchanges.

In Rostov-on-Don, Russians accused 22 POWs of “participation in a terrorist organization” and “actions aimed at power takeover.” Thus, Russia openly violates not only the 2022 agreement, but also the rights of prisoners of war guaranteed to them by international humanitarian law.

In particular, Russia violated the rights of Azov soldiers as combatants guaranteed to them by Article 43 of the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 for the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts.

SEE ALSO: To Defeat Russian Fascism, It Must Be Given a Name

Combatants (legitimate participants in hostilities) are not subject to criminal prosecution and punishment by the enemy party to the international armed conflict for their participation in hostilities.

The Russian authorities committed a war crime under Article 130 of the 1949 Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War and Article 8 of the Rome Statute, in the form of depriving prisoners of war of the right to a fair trial.

It is symbolic that Russia is committing its violation of international humanitarian law on the opening day of the 2nd Hague Conference of 1907, which resulted in the adoption of 13 international conventions, including the Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, which established clear criteria for distinguishing between combatants and non-combatants.

Arranging a trial of prisoners, Russia incriminates them not personally committed actions, but the very participation in Azov, groundlessly declared a “terrorist organization” in Russia. (According to media reports, the women who were selected for the trial were working as cooks in the Azov regiment.) Another charge — “actions aimed at seizing power” — concerns the “guilt” relating to the illegal Russian occupation administration in the temporarily occupied territories of Donetsk Oblast of Ukraine, which cannot be covered by Russian legislation.

In contrast, all cases of trials of Russian prisoners of war in Ukraine took place solely on charges of criminal acts personally committed by these servicemen, and not for their belonging to certain formations of Russian law enforcement agencies.

The decision to start the Rostov trial is obviously connected with the intensification of hostilities in Ukraine and Russian defeats at the front. Russians actually turned prisoners of war into hostages, whose fate should become, according to the Kremlin’s plan, a subject of political bargaining, as is customary among terrorists.

The actions of all officials involved in the Rostov trial will receive a proper legal assessment from both Ukraine and the international community.

Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and pressing Ctrl+Enter.